Every writer, at some point, has gone 'I'd like to try something new' or 'I've always wanted to write X', but where to start?' You can watch/read your favourites, take notes and study them, but what if you need something more specific? Some type of reference or guidelines, even just something to quickly highlight common tropes you can avoid or find new spins on?

Well, writing guides to just about every genre in fiction exist, old and new, and many authored by working veterans, are available. Of course, the sheer volume (and then factoring in sites like Amazon permitting self-published works) can be rather daunting and confusing for a newcomer to disentangle. Well today, I'll give that a shot with an easy list of published works: a mix of personal recommendations and ones I've heard on the grapevine.

This article, for the sake of disclosure, is not sponsored by anyone mentioned - this is just me and me alone.

To be clear, this is not a comprehensive or exhaustive list of genre writing guides, nor is this one about storytelling basics (your Save the Cats etc): I already covered that elsewhere. This is also not a guide to books on entire mediums like film, stage and TV (save one example which I'll explain), career advice (at least, not chiefly) or memoirs by famous writers - this is just for storytelling genres.

There will also be no self-published works (the quality threshold, never mind the sheer number of them, is just too all over the place to be useful or consistent) and I will avoid too many books from within the same series (Teach Yourself and For Dummies do include a number of these guides, if you want an immediate starting point). Last, I will also include, as and when relevant, essay compilations, though this will be geared in the direction of practical writing advice, rather than purely analytical writing.

Crime/Mystery:

- Writing Crime Fiction by Rosemary Atkinson

- How to Write a Damn Good Mystery by James Frey

- How to Write a Mystery: A Handbook edited by Lee Child with Laurie R. King

- Writing the Cozy Mystery by Nancy J. Cohen

- Writing the Mystery: A Start to Finish Guide for Both Novice and Professional by G. Miki Hayden

Thrillers:

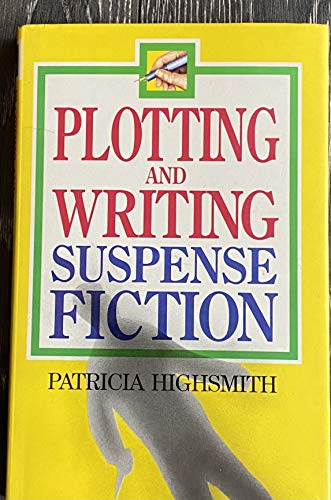

- Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction by Patricia Highsmith

- Writing and Selling Thriller Screenplays: From TV Pilot to Feature Film by Lucy V. Hay

Fantasy/Sci-fi:

- Wonderbook by Jeff Vandermeer

- Get Started in Writing Science Fiction and Fantasy by Adam Roberts

- Making Myths and Magic: A Field Guide to Writing Sci-Fi and Fantasy Novels by Shelley Campbell and Allison Alexander

- Writing the Science Fiction Film by Robert Grant

- Writing Fantasy and Science Fiction by Brian Stableford

- On Writing Horror: A Handbook by the Horror Writers Association, edited by Mort Castle

- A Sense of Dread: Getting Under the Skin of Horror Screenwriting by Neal Marshall Stevens

- Horror Screenwriting: The Nature of Fear by Devin Watson

Comedy:

- How To Write Comedy by Tony Kirwood

- The Serious Guide to Joke Writing by Sally Holloway

- Elephant Bucks: An Insider's Guide to Writing for TV Sitcoms by Sheldon Bull

- The TV Writer's Workbook by Ellen Sadler

- The Complete Comedy Writer by Dave Cohen

- The Hidden Tools of Comedy: The Serious Business of Being Funny by Steve Kaplan

Romance:

- Writing and Selling - Romantic Comedy Screenplays by Craig Batty & Helen Jacey

- Writing a Romance Novel For Dummies by Victorine Lieske and Leslie Wainger

- (Interestingly, I've noticed romance seems especially dominated by self-published guidebooks. If you wish to give them a go, well, have at it. Just check out the author's credentials to see they are legit.)

Children's/Animation:

- Writing for Animation by Laura Beaumont - my one cheat on this list as animation is a medium, not a genre unto itself. However, writing is a criminally underdiscussed part of the animation and few blogs and websites mention it either. There's also incredibly few books discussing children's stories, so another strike.

- Writing for Animation, Comics, and Games by Christy Marx

- Animation Writing & Development: from script development to pitch by Jean Ann Wright

- Directing the story: professional storytelling and storyboarding techniques for live action and animation by Francis Glebas

- How to Write for Animation by Jeffrey Scott

- Creating Animated Cartoons with Character by Joe Murray (thanks to Liam Swann for these suggestions!)

- The Magic Words: Writing Great Books for Children and Young Adults by Cheryl B. Klein

- Writing for Children by Pamela Cleaver

- Writing Picture Books by Ann Whitford Paul

Hope this little compilation has helped guide you on the right road!